125 years of rugby league – yet it still isn’t enough

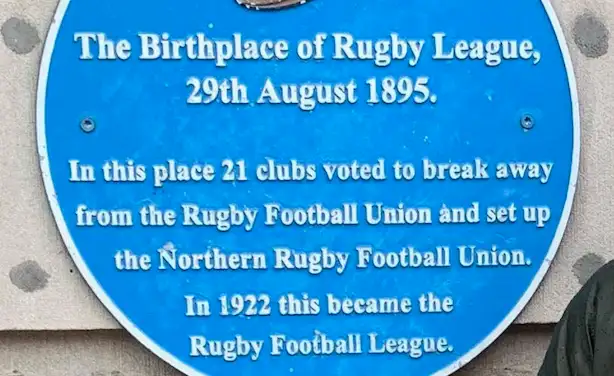

There are incredible tales from throughout rugby league’s 125 years, all underpinned by its foundation and the adversity it has almost always faced since.

That context must always be remembered. Two codes of rugby exist because the northern clubs wanted to pay players to compensate them for the loss of work.

One of its most fascinating tales is told in The Forbidden Game, surely one of the greatest sports books ever written, which provides a context that is still pertinent today.

Any person debating the expansion of rugby league must read this book. Even aside from its main topic, emphasises the cultural foundation of the game; methods of expansion; and for me further demonstrates how RL doesn't do enough to embrace and support the French domestic comp. pic.twitter.com/gOKvMfJxIZ

— James Gordon (@jdgsport) August 23, 2020

Sick of rugby union’s cover-up of their blatant professionalism (shamateurism), rugby league was forged in France and thrived until the Second World War, when the Vichy Government banned it, in the most disgraceful instance of persecution that the game suffered – persecution that has perhaps only mellowed in recent memory.

A collection of French players came to England to play, and learn, the game. Internationals, including an England v Australia test, were held in France to grow the game. There was a league of professional clubs, underpinned by hundreds of amateur clubs. While it’s a different era, the methods of how rugby league blossomed in France could still be learned from today – albeit, there are more differences between the two codes today.

Reading that book, you can’t help but wonder about the development of the sport and the situations of today.

If Super League fails, that doesn’t mean rugby league is dead. Rugby league will always exist. In what form it exists may change from time to time, but that has always been the case.

For every high-profile expansion fail – the underlying reasons for which still haven’t been addressed or analysed – there are literally hundreds of grassroots clubs that have sprung up around the British Isles, that emphasise that the game goes beyond its traditional “heartlands.”

Just this morning in fact, we received a press release from North East club Cramlington Rockets, celebrating their 20th birthday and detailing its achievements along the way – including that they now have more than 230 players in their club and do work with more than 30 local schools and community groups to promote rugby league.

This organic and strategic growth, of which the North East is surely at the forefront of, is what the game needs – as opposed to its incoherent bumbling between unfounded pipe dreams that risk alienating what it already has – as I’m sure fans in places like Oldham, Workington, Halifax and even Bradford might well testify.

On the doorstep

Bradford is an interesting case. A club based in a city – of which we’re told we need more of – with a rich and illustrious history, even in recent times; catastrophically managed to the extent that it went all the way down to the third tier and now plays games at Dewsbury. That highlights how difficult it is for any expansion team to establish themselves in a way everybody hopes and dreams that they can.

The problem isn’t expansion – it’s that the expansion is trying to be done with little thought or strategy; or without having looked after and nurtured the foundations to enable it to grow.

Newcastle are, and will be, a fine example of that. Still a third tier club, but in a big city, there’s a clear strategy to get Thunder up the leagues with a pathway around them – and while they may not hit their bold target of winning Super League by 2030, reaching the top flight with a clutch of homegrown players in that time and sustaining it, may well be a bigger win for rugby league on the whole.

Rugby league hasn’t yet made significant in roads in to two major cities on its door step, despite the best efforts of community clubs in Manchester – an attempt to rebrand a professional club was (probably rightly) rebuked by its own fans, yet a movement to add Manchester Rangers to League 1 several years ago was thrown out due to the presence of four other clubs in the Manchester region.

The change in demographic over the past half a century, particularly in Yorkshire towns, doesn’t seem to have been embraced either. The strong Asian community that live side by side with long standing rugby league people have, for the main part, yet to be captured by the “greatest game”, without ignoring the efforts of those like Ikram Butt who have tried to get the wheels in motion.

Greed over growth

Yet here we are, blinded by the bright lights of anyone who might have a few dollar bills to throw at the game, no matter how outlandish the suggestion. Rugby league’s recent disingenuous expansion efforts have been motivated by greed.

The obsession is with hypothetical sponsorship and broadcast deals, of which there appears to be little evidence of probability even with a relatively smooth introduction to new markets, to find money to “save” the game, rather than for actually spreading the gospel of rugby league.

Whatever happens with Toronto moving forward, their efforts will be marred – at least in the short term – by the numerous episodes of concern from recent times, be it not paying players or suppliers, visa problems and of course, not fulfilling its fixtures. Like it or not, what’s gone on so far will put doubts in the mind of any hypothetical partners.

It’s probably just rugby league’s luck that the year when its brave commitment to Trans-Atlantic competition was going to start hopefully reaping its rewards, that a global pandemic hit.

Hopefully a more organic approach will be found, one that can embrace grassroots rugby league in Canada and North America, and ensure the development of the domestic league over there, as well as any professional franchises it has – with genuine investment in the infrastructure, facilities and player pool around it.

Embrace what is already there

In rugby league’s attempts to be what it thinks people (by people – the wider public, sponsors and broadcasters) want it to be, it has lost its identity.

Gone are the tours that are landmarks of rugby league’s past. International matches are few and far between, despite the fact that 80 odd years ago, the same countries we have player pools in today (France and Wales) were playing regular matches.

Not every match will be the perfect test for England. But rugby league will never be perfect. It was founded as a breakaway from another sport. We don’t need expansion to be able to have more genuine international matches – rather than them being an after thought tagged on to the end of the season.

Even without COVID, we would have gone two years without an England international.

While the game, as everything, must expand to keep going forward, that doesn’t mean that in the meantime it shouldn’t maximise what it currently has. The efforts made by the 2021 World Cup team has that in spades, yet either side of that, we’re still lacking any meaningful or regular international fixtures that must surely now be prioritised in the calendar.

The NRL’s yearn to be comparable to the big four leagues across the pond – if not quite in financial might or stature, but relatively speaking – has them prioritising their own competition over everything else. In many ways, that’s fine.

One of rugby league’s problems is doing everything as a collective and trying to please everyone all of the time. What’s best for the growth of rugby league, might not be what’s best for the growth of the NRL or indeed of Super League. The actions required by the RFL for growing the game in Canada probably aren’t, for instance, the best actions for clubs in England.

Despite what Twitter says, there isn’t anybody who doesn’t want the game to grow. Once bitten, twice shy.